About the survey

The VLSB+C is committed to regularly conducting surveys to hear Victorian lawyers’ perspectives on systemic issues affecting the profession.

In recognising that there was limited contemporary research on supervised legal practice (SLP), in 2023, we surveyed early career lawyers about their experience of this vital period of professional development.

They shared rich insights into how they were managed and supported by their supervisors during SLP, and the challenges they faced.

To make sure we gained a balanced understanding of SLP, in 2024 we asked supervisors about their experience of supervising early career lawyers.

A total of 409 lawyers who have supervised a lawyer within the last five years took part in our voluntary survey. All questions were optional, so not all survey questions had the same number of responses. The total number of responses to any one question ranged from 281 to 354, and on average, each question had 299 responses.

As some supervisors may have supervised more than one lawyer, we asked them to respond to the survey with their most recent supervisee in mind.

We would like to thank the lawyers who took part in these surveys for sharing their perspectives. The survey results will be used to inform initiatives to better support early career lawyers, and the lawyers who supervise them.

*Headline results

The supervisor survey results include many encouraging findings about their views on SLP.

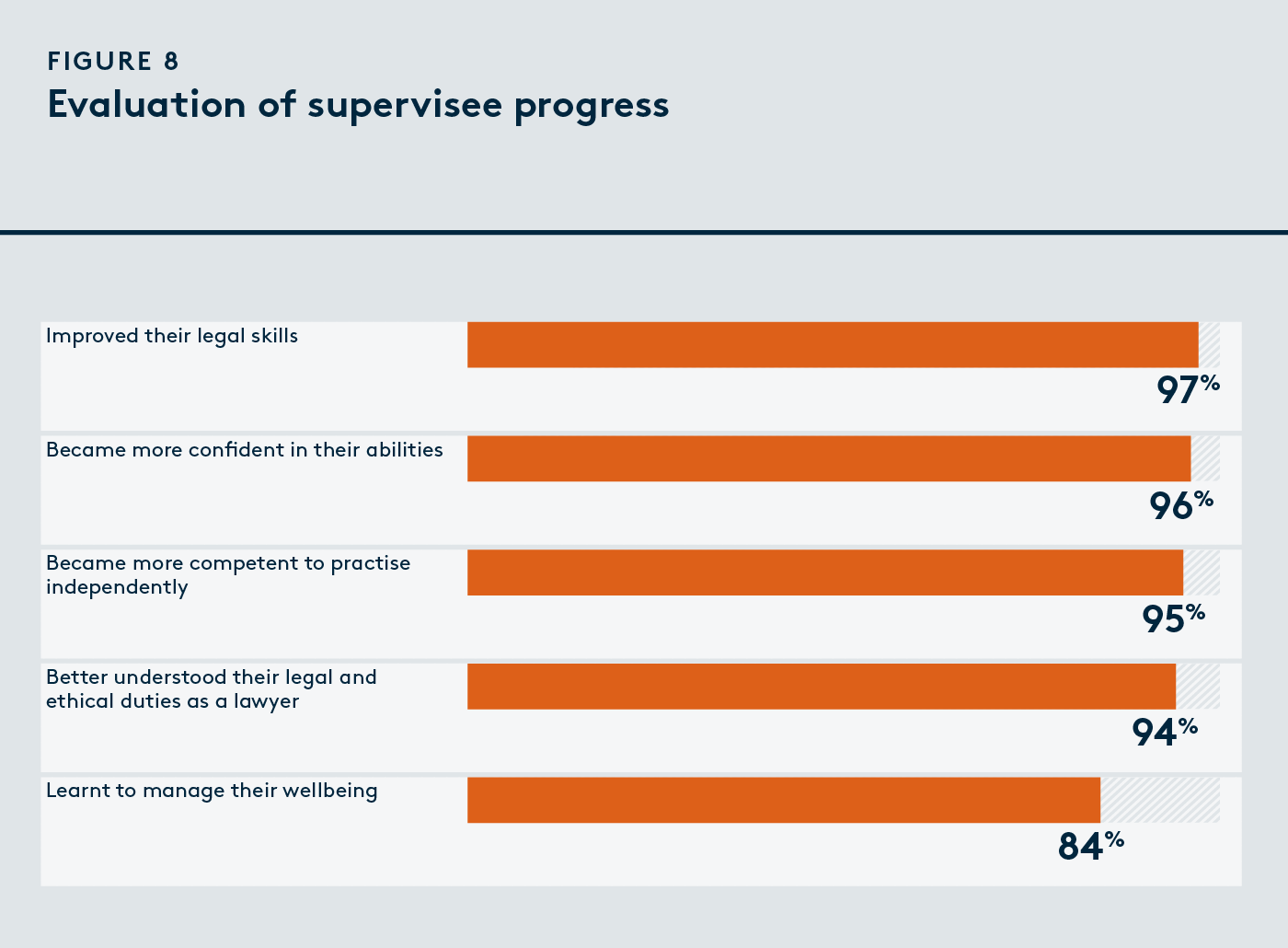

When asked whether their supervisee made improvements under their supervision, the overwhelming majority agreed or strongly agreed that their supervisee:

- improved their legal skills (97%)

- became more confident in their abilities (96%)

- became more competent to practise independently (95%)

- gained a better understanding of their legal and ethical duties (94%)

- learnt to manage their wellbeing (84%).

It was positive to see that most supervisors met frequently with their supervisee, with nearly three in four (73%) meeting daily or weekly, 60% spending 45 minutes or more with their supervisee each week, and all supervisors having ad-hoc meetings with their supervisee. Most lawyers (78%) said that the time they spent meeting with their supervisee was enough for their development.

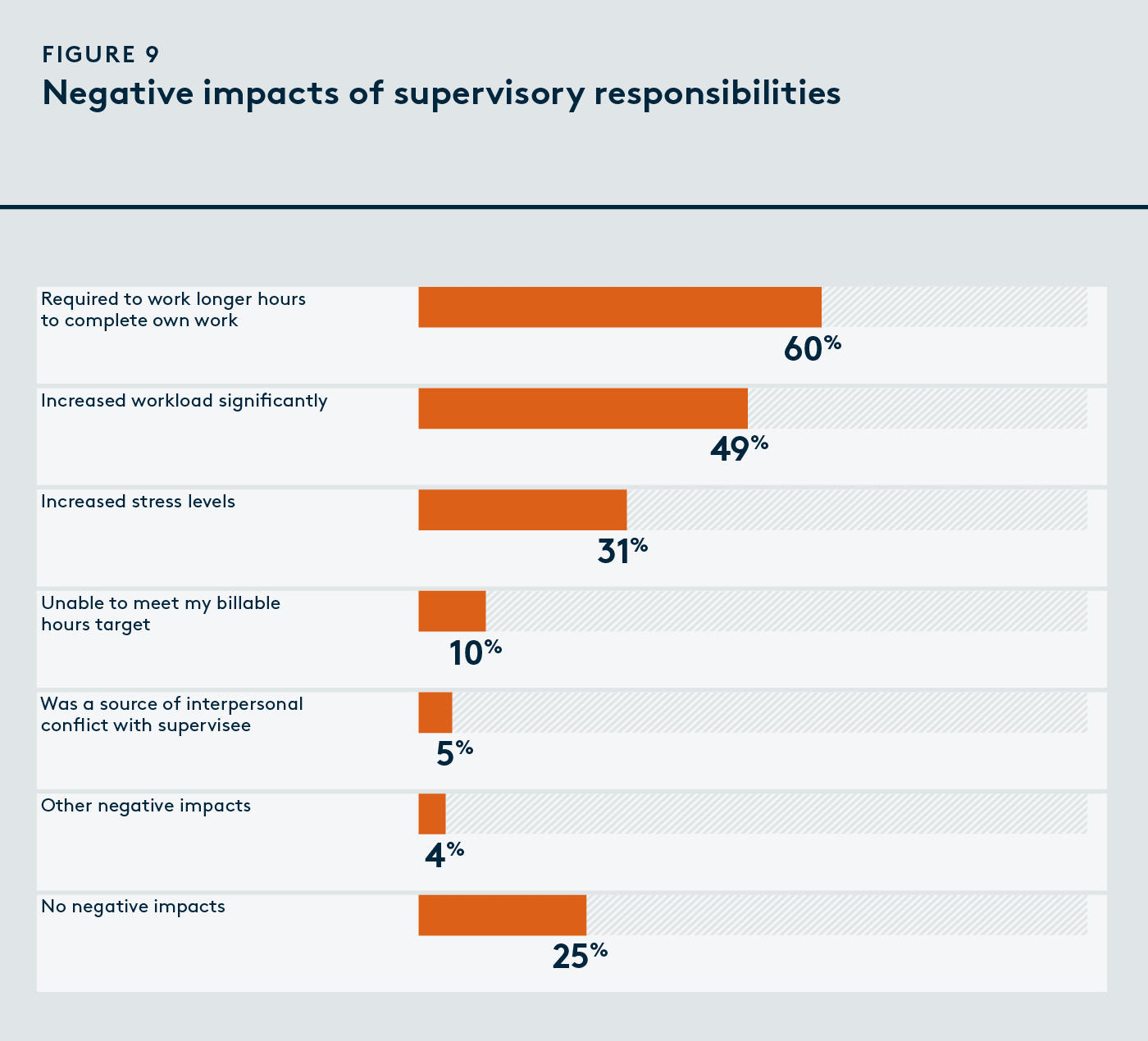

However, the survey findings also highlight challenges. Importantly, most supervisors (75%) told us they were negatively affected by their most recent supervisory responsibilities in some way. For three in five supervisors (60%), the role required them to work longer hours to complete their own work, and almost half (49%) said that those responsibilities significantly increased their workload. For close to one third (31%), their supervisory responsibilities increased their stress levels.

Detailed results

Supervisor demographics

Most survey respondents were women (59%) followed by men (40%) and people identifying as non-binary or people using another term (1%).

One third (33%) of respondents were aged 30–40 years, 28% were aged 41–50 years, 15% were aged 51–60 years, 14% were aged 61–70 years, 8% were aged over 70 years, with only 2% aged 20–30 years.

At the time they completed the survey, 73% of respondents had more than 10 years of post-admission experience (PAE). One in five (20%) had 11–15 years, 18% had 16–20 years and 35% had over 20 years of PAE. Of the remaining respondents, 23% had 6–10 years and 4% had 0–5 years of PAE.

Experience, training and perceptions of supervision

Practising and supervision experience

Encouragingly, most supervisors had extensive PAE when they first started supervising lawyers under an SLP condition. Over a third (39%) had more than ten years, followed by 29% with 6–10 years and 27% with 3–5 years. A small number of supervisors (5%) said that they had 0–2 years of PAE when they first took on these responsibilities.

We asked supervisors how many lawyers they had supervised overall, and the average duration of their supervision. On average, they had supervised six lawyers, and their supervisory relationships each lasted 14 months.

Most supervisors held supervisory responsibilities for several years. The majority had supervised other lawyers under an SLP condition for 3–5 years (29%), 18% for 6–10 years, and 25% for more than 10 years. Only 11% of supervisors had supervised for less than a year at the time they completed the survey, with another 17% having supervised others for 1–2 years.

Training in supervision

Less than half of supervisors (41%) had undertaken external training in supervision. Of those who had, 66% found it useful or very useful. By comparison, nearly half (49%) had undertaken workplace training in supervision, and of this group, 72% found it useful or very useful. Most supervisors (70%) had been mentored in supervision by other lawyers, and among those who had, 80% found it useful or very useful. The majority of supervisors (81%) had also learned about supervision by observing other lawyers supervising, and of this group, 86% found it useful or very useful. More than two in three supervisors had accessed our resources on supervision, with 67% having accessed our supervisor guidelines (69% of whom found them useful or very useful), and 69% having accessed our SLP Policy (66% of whom found it useful or very useful).

Perceptions of the importance of supervisory responsibilities

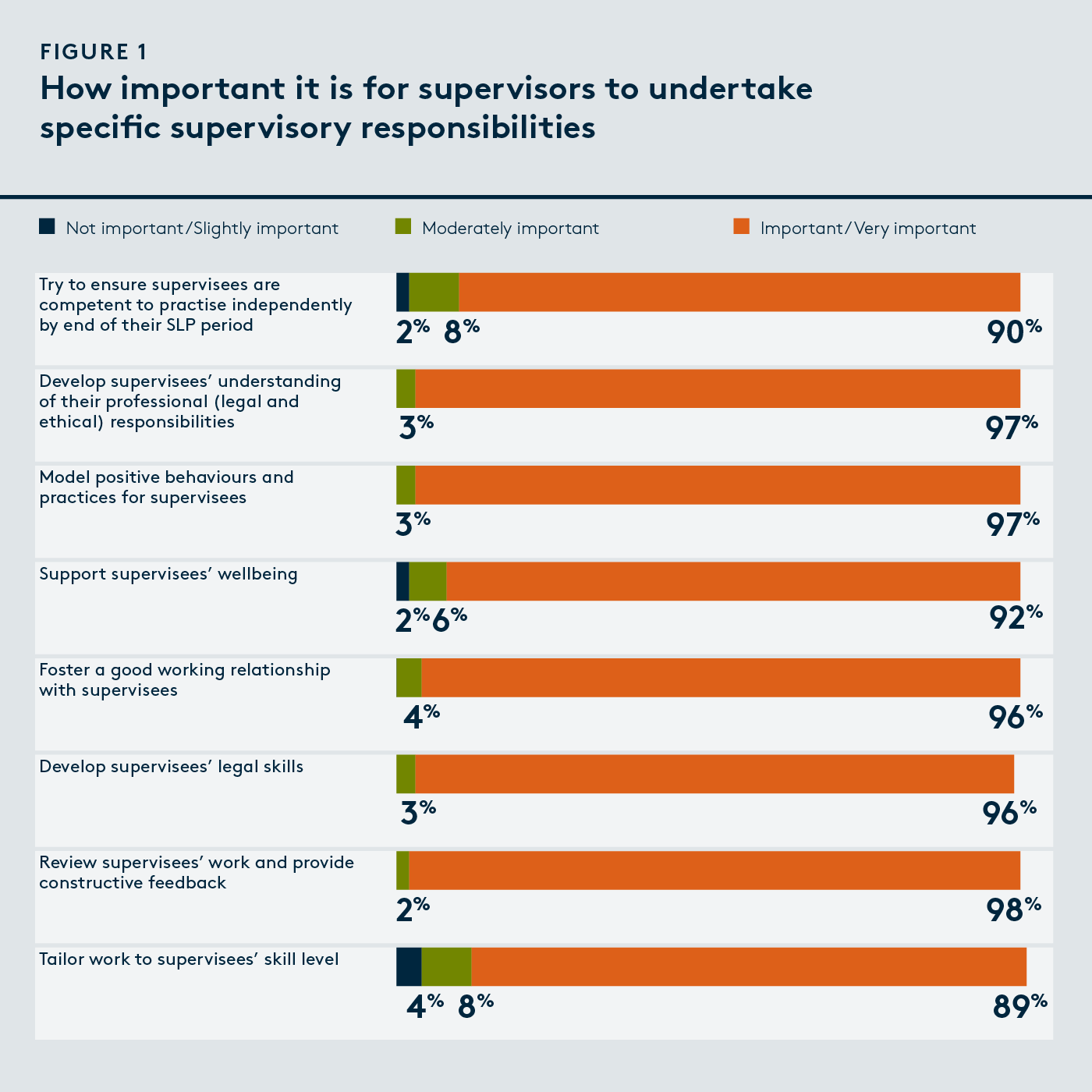

We also asked lawyers about their views on how important it is for supervisors in general to undertake specific supervisory responsibilities (e.g. tailoring work to their supervisee’s skill level, supporting their supervisee’s wellbeing). Encouragingly, the vast majority (89–98%) told us that it is important or very important for supervisors to perform all of the specific supervisory responsibilities (for the full list, see Figure 1).

Workplace characteristics

We asked supervisors about the workplaces where they most recently supervised a lawyer under an SLP condition.

Most were located in Melbourne’s CBD (57%) followed by Melbourne’s suburbs (26%) and regional Victoria (15%). A small percentage (2%) worked in another area (e.g. a workplace operating across more than one state).

Various kinds of workplaces were represented in the results. Most supervisors supervised another lawyer within a law practice (39%), with others having supervised in government employers (19%), incorporated legal practices (16%), community legal services (11%), non-legal employers (8%), sole practitioner law practices (5%) and other types of workplaces (2%).

Most workplaces had more than 40 employees (45%) followed by 1–5 employees (20%), 11–20 employees (15%), 21–40 employees (10%) and 6–10 employees (9%).

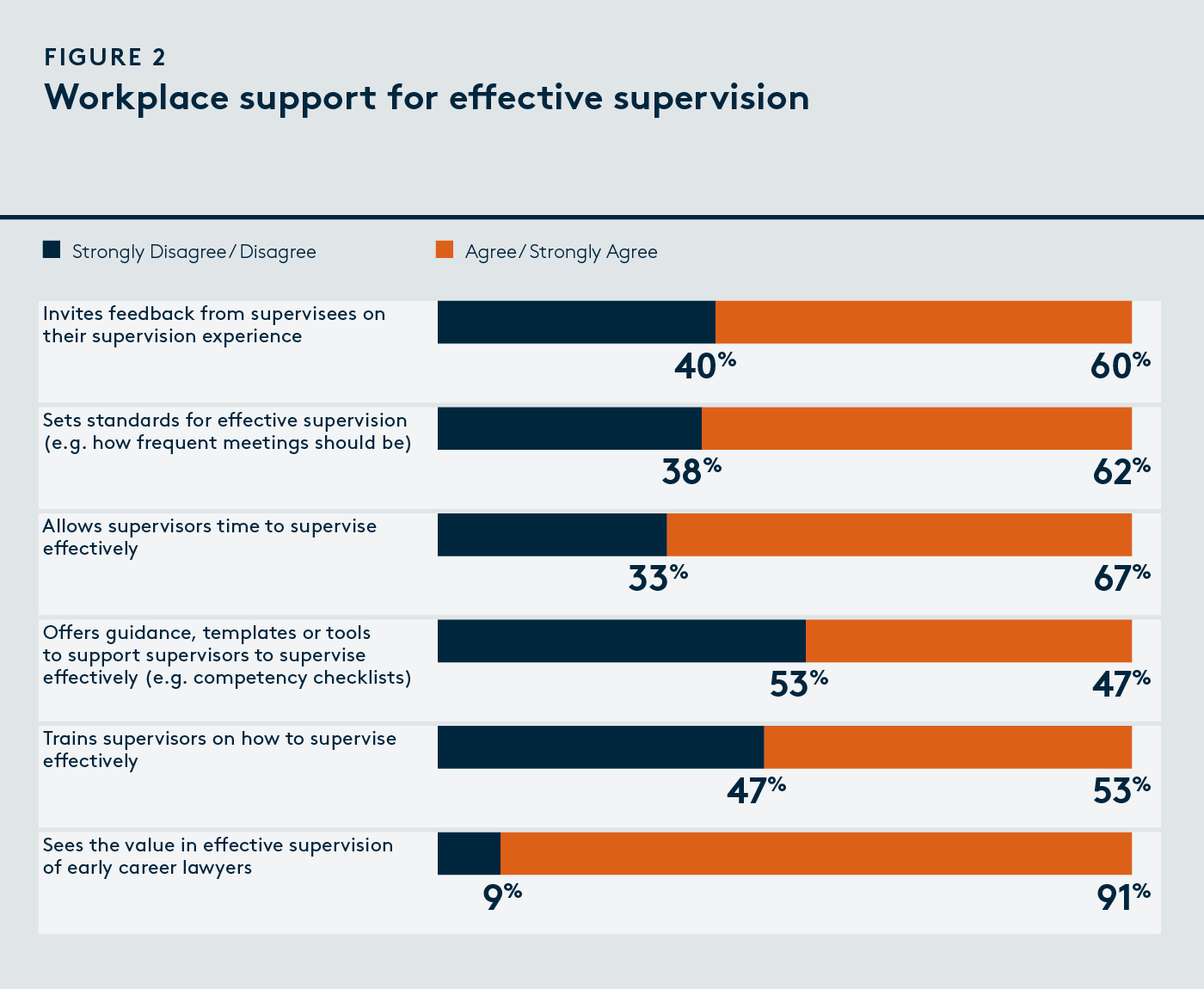

We asked supervisors how their workplace supported them in their supervisory role. Most (91%) agreed that their workplace saw the value in effective supervision of early career lawyers. Interestingly, this did not necessarily translate into their workplace providing practical support. Almost half (47%) did not receive workplace training in how to supervise, and one in three (33%) were not provided with enough time to supervise effectively. Less than half (47%) said that their workplace provided them with guidance, templates or tools to supervise effectively (see Figure 2).

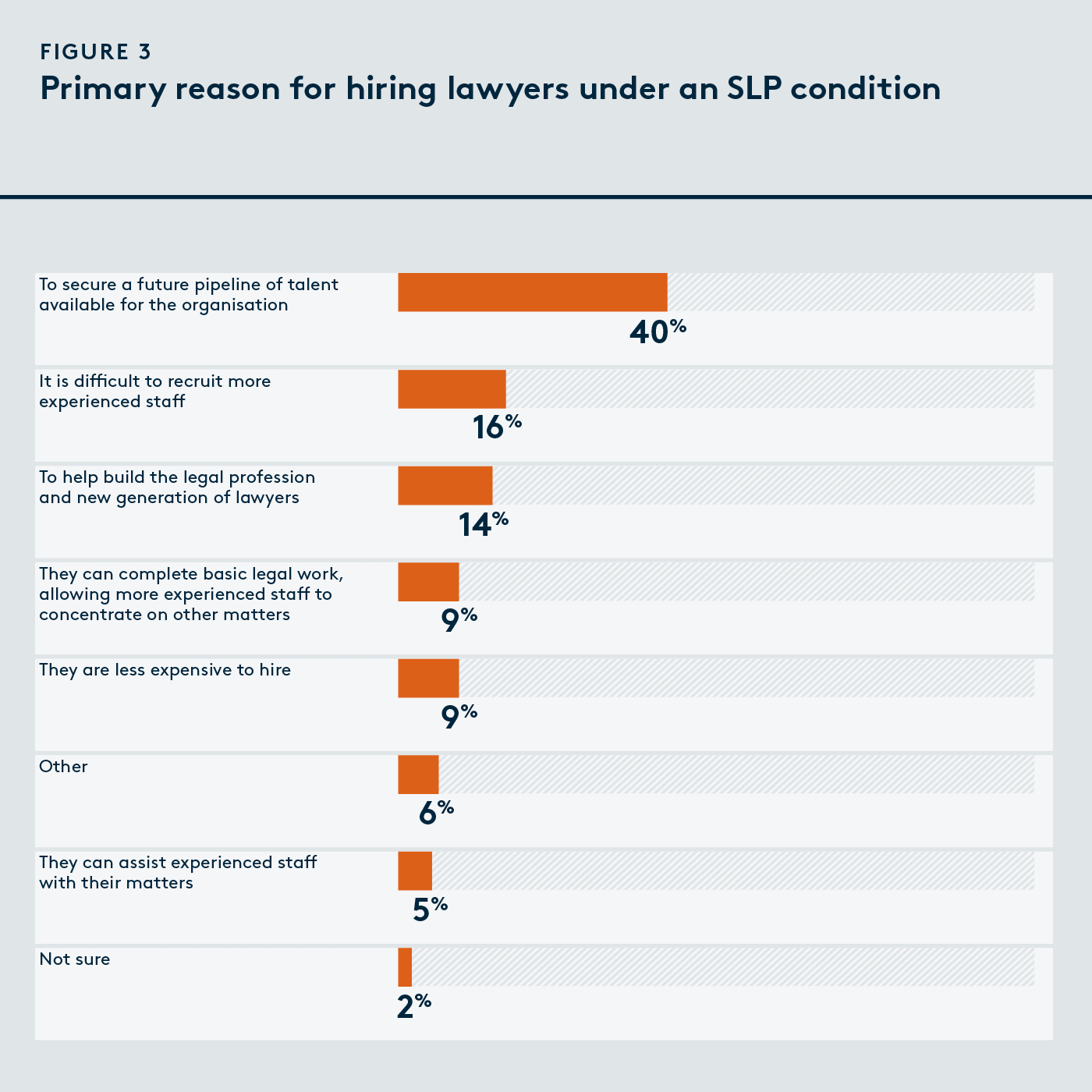

We asked supervisors what they thought their workplace’s primary reason was for hiring lawyers under an SLP condition. Most (40%) thought that the main motivation was to secure a future pipeline of talent available to the organisation (see Figure 3). Other reasons included:

- the difficulty in recruiting more experienced staff (16%)

- the desire to help build the legal profession and a new generation of lawyers (14%)

- that lawyers under SLP:

- are less expensive to hire (9%)

- can complete basic legal work, allowing more experienced staff to concentrate on other matters (9%).

Starting the supervisory relationship

When we asked lawyers why they had supervised their most recent supervisee, nearly two in three (61%) told us that supervision was part of their position description and/or job responsibilities. Nearly one third volunteered to supervise (30%), either because they enjoyed mentoring and teaching early career lawyers (16%), thought it was important to develop a new generation of lawyers (12%), or because they wanted to further develop their own professional skills (2%).

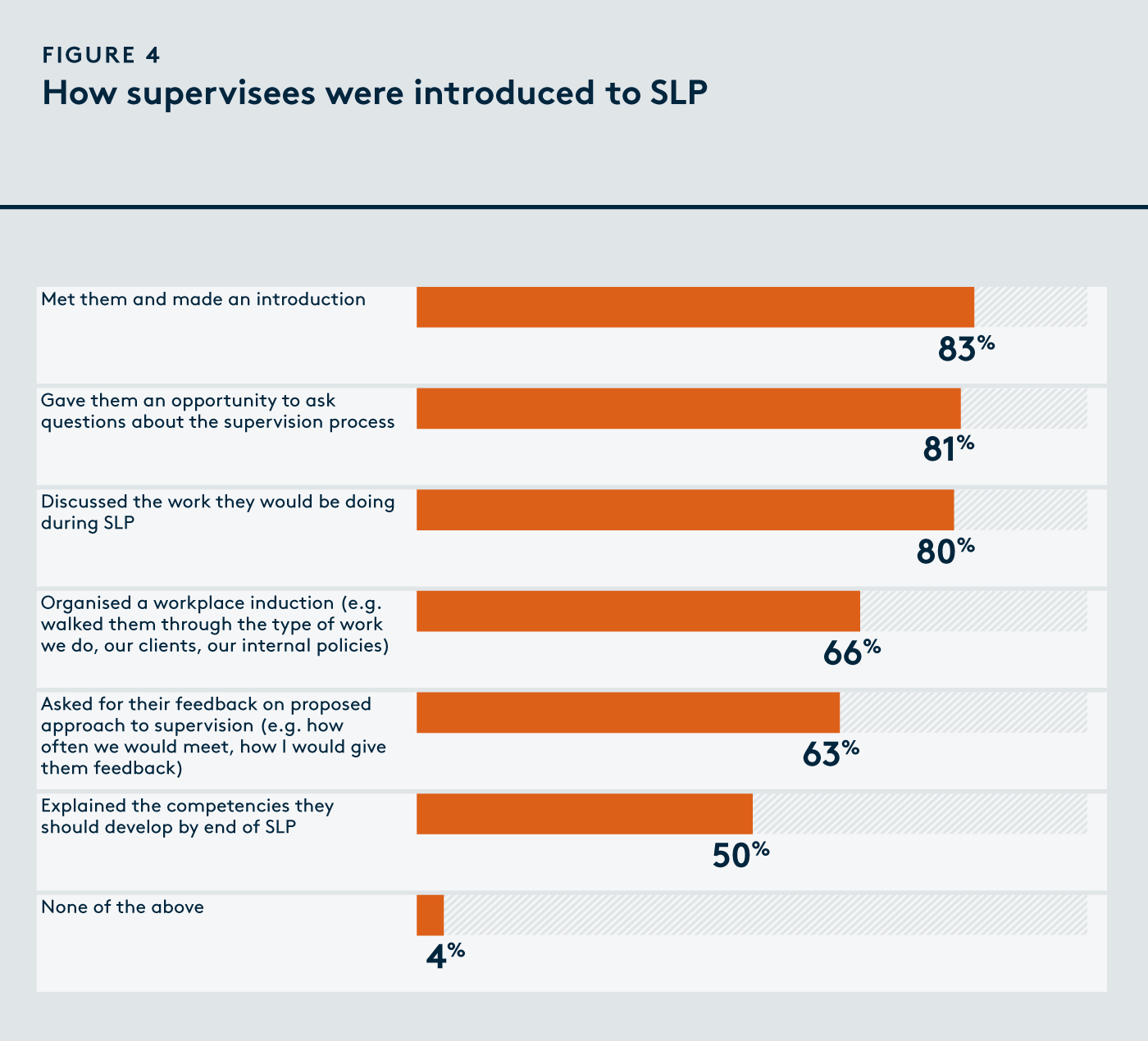

We also asked supervisors about the actions they took when they started supervising their most recent supervisee. Pleasingly, the vast majority (96%) told us they took proactive steps to introduce their supervisee to the supervisory process. Most introduced themselves to their supervisee (83%), gave them the opportunity to ask questions about the supervision process (81%) and discussed the work they would be doing during SLP (80%) (for the full list, see Figure 4).

Day-to-day supervision

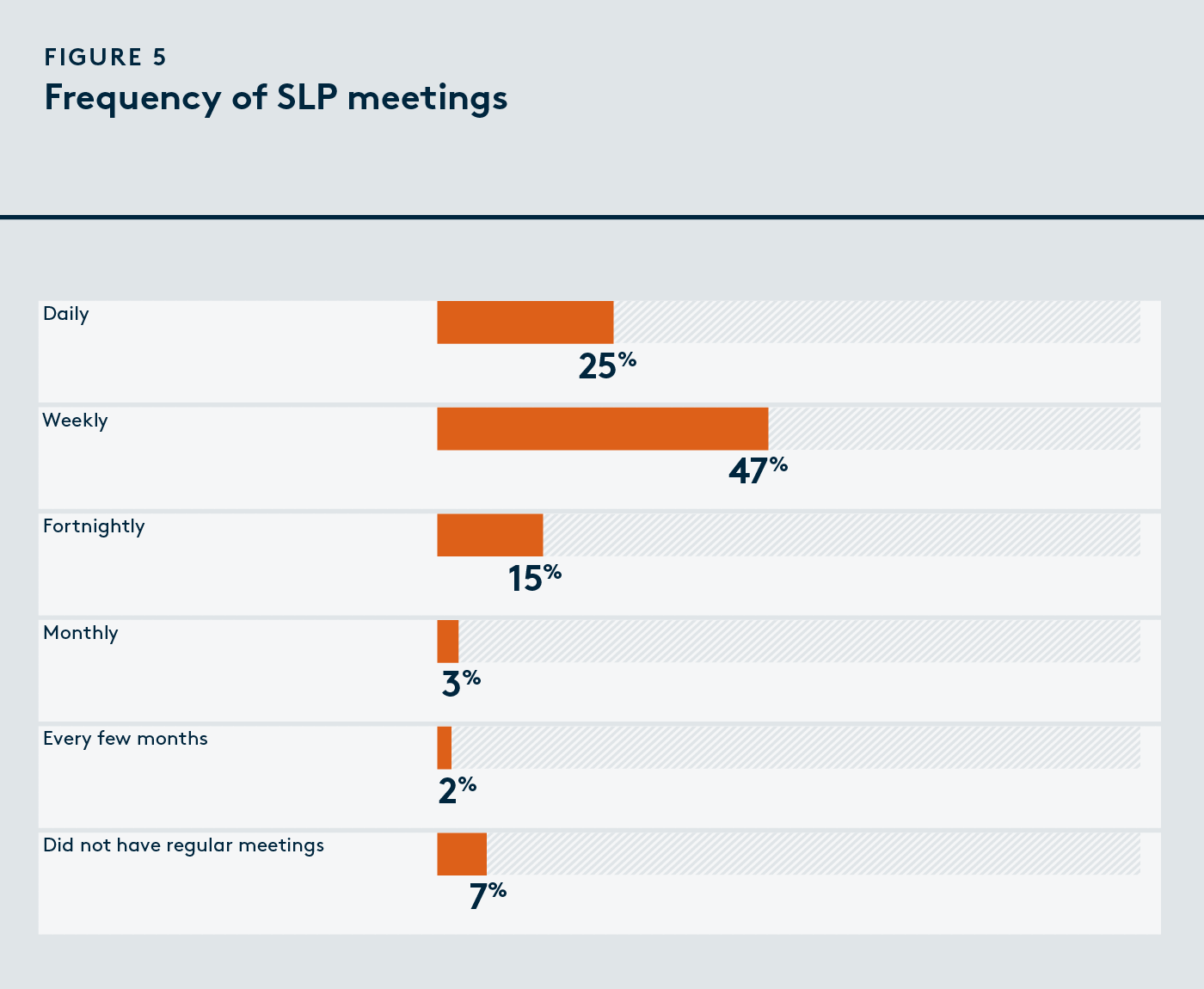

We asked lawyers about their day-to-day experiences of supervision. When asked how regularly they scheduled meetings with their supervisee, 92% told us that they met regularly. The frequency of regular meetings, however, differed widely, with 25% meeting with their supervisee daily, and the majority (47%) holding weekly meetings. Another 15% met with their supervisee fortnightly, with small percentages having meetings every month (3%) or every few months (2%). Notably, 7% told us that they didn’t meet regularly with their supervisee (see Figure 5).

Outside the structure of regular meetings, all supervisors had ad-hoc meetings with their supervisee. Nearly all (97%) told us that their supervisee could come to them at any time for assistance, and 36% had ad-hoc meetings specifically to give their supervisee feedback outside of their scheduled meetings.

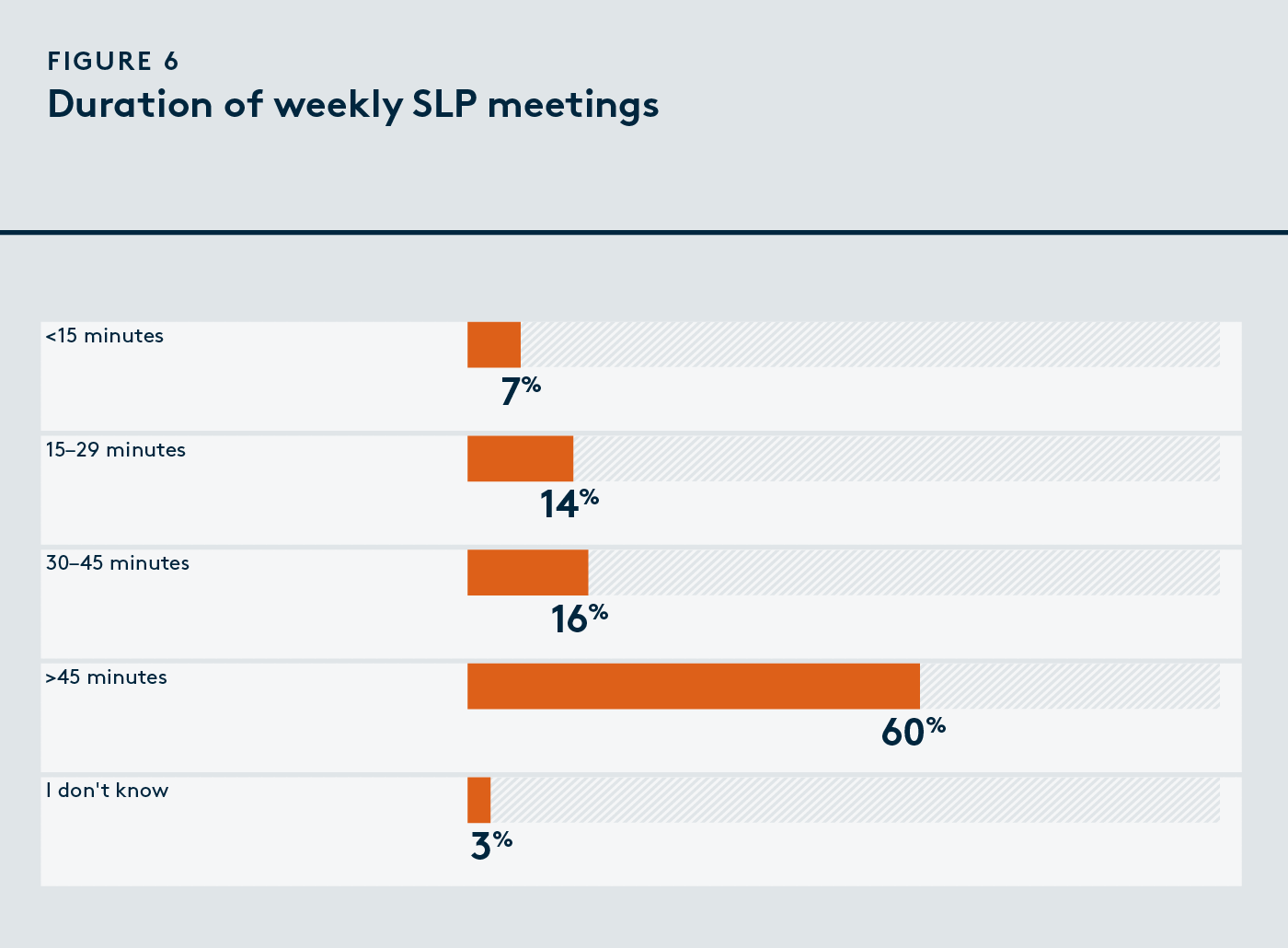

Most supervisors (60%) told us that they spent at least 45 minutes with their supervisee each week, whereas only 7% spent less than 15 minutes (for more details, see Figure 6).

Most supervisors (78%) thought they spent enough time with their supervisee, whereas 21% would have preferred to spend more time. Only 2% of supervisors believed they spent more time with their supervisee than was necessary.

When we asked lawyers how supervision meetings were usually held, 76% told us that they met with their supervisee in person, 21% held meetings via video conference and 3% spoke over the phone. Nearly all (98%) felt that the method they used was effective.

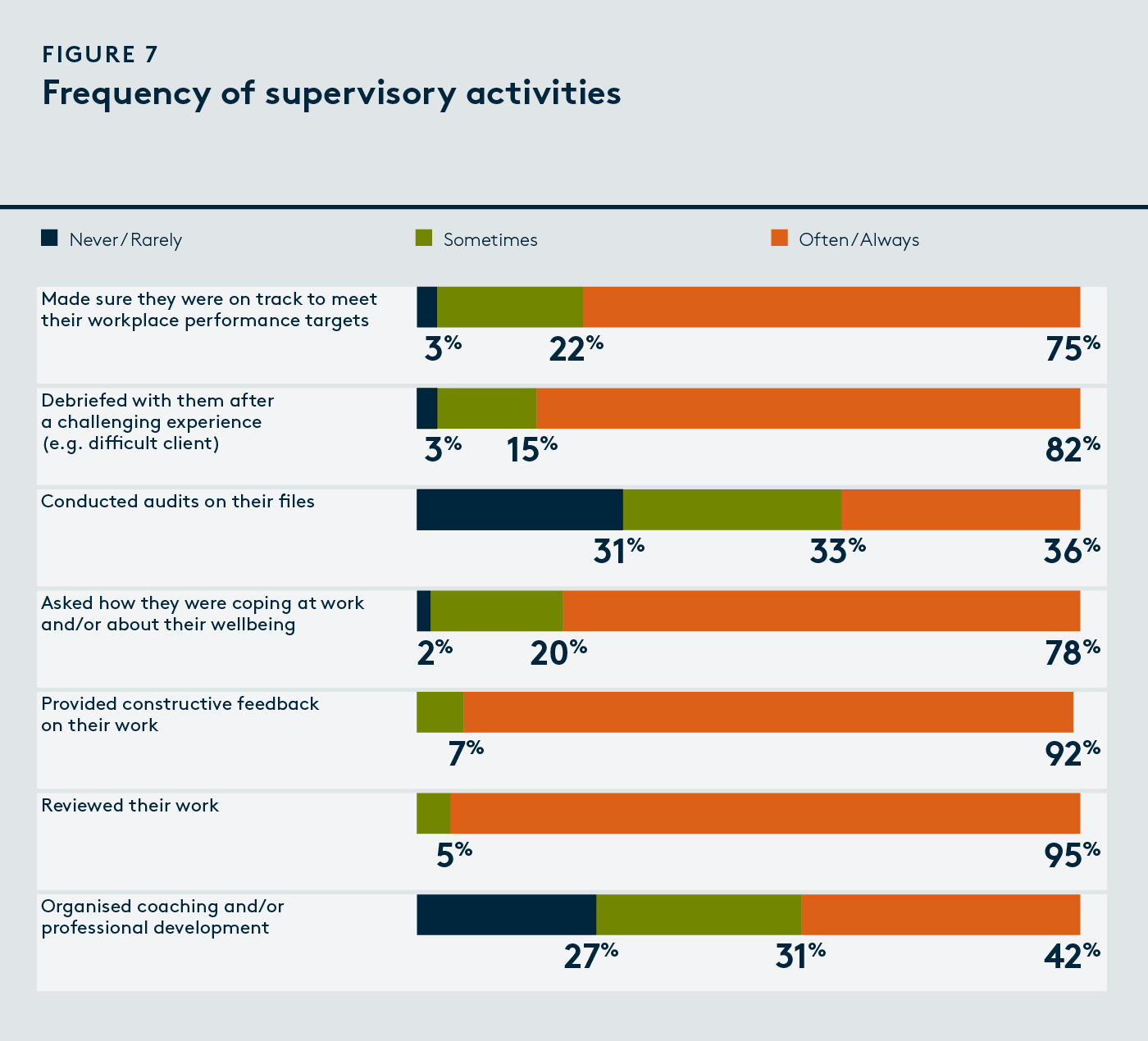

We also asked supervisors how often they carried out certain supervisory activities. Positively, the vast majority (95%) often or always reviewed their supervisee’s work often, and 92% often or always gave constructive feedback. There were also positive findings about the approaches supervisors took to looking after the wellbeing of their supervisee. Most (82%) often or always debriefed with their supervisee after a challenging experience (e.g. a difficult client) and 78% often or always asked how their supervisee was coping and/or asked about their wellbeing (for more details, see Figure 7).

Evaluating the progress of supervisees

We asked lawyers whether, under their supervision, their supervisee improved their skills, confidence and wellbeing. Overwhelmingly, supervisors agreed or strongly agreed that their supervisee’s skills and confidence as a lawyer improved. However, slightly fewer supervisors agreed or strongly agreed that their supervisee learnt to manage their wellbeing (for more details, see Figure 8).

We also asked lawyers how they assessed the effectiveness of their supervision. The vast majority (92%) made their assessment through personal observation of their supervisee’s progress, and 4 in 5 (81%) directly sought feedback from their supervisee. Other common approaches were to seek feedback from colleagues (62%) or clients (51%) on the quality of their supervisee’s work. Only 27% of supervisors assessed their supervisee’s progress against a competency framework or checklist.

Personal costs and benefits of supervision

We asked lawyers about the personal costs and benefits of being a supervisor.

Importantly, most (75%) told us that their supervisory responsibilities negatively affected them in some way, including by:

- requiring them to work longer hours to complete their own work (60%)

- increasing their workload (49%)

- increasing their stress levels (31%) (for more details, see Figure 9).

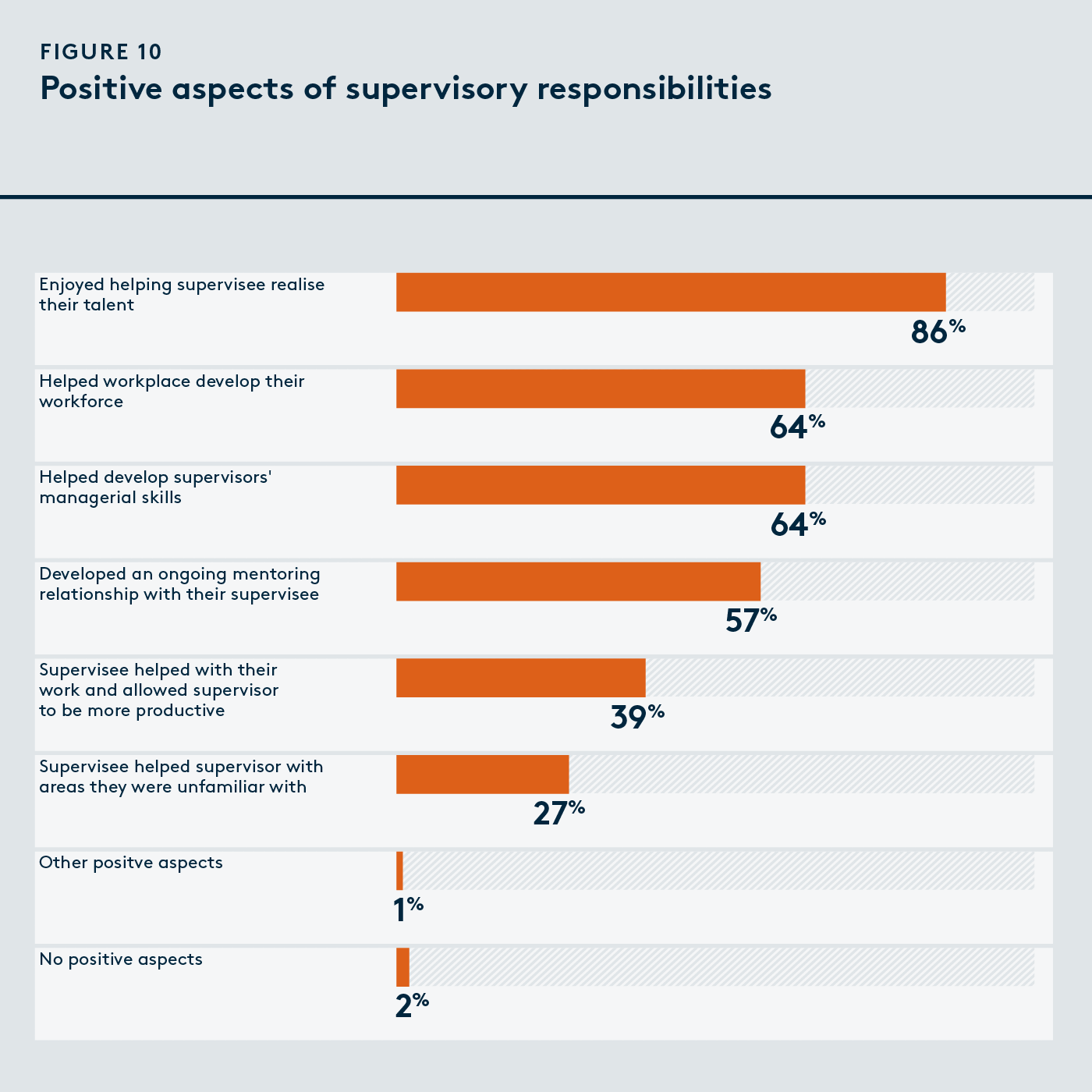

Despite the increased workload and, for some, the stress associated with being a supervisor, nearly all supervisors (98%) told us that their recent supervisory responsibilities had some positive aspects. Most (86%) enjoyed helping their supervisee realise their talent, and 64% said that by supervising another lawyer, they helped their workplace develop its workforce. Another 64% of lawyers said that supervision helped develop their managerial skills and more than half (57%) developed an ongoing mentoring relationship with their supervisee. Pleasingly, 39% of lawyers told us that their supervisee helped them with their work and allowed them to be more productive (for more details, see Figure 10).

Barriers and opportunities for improvement

In the final part of the survey, we gave lawyers the opportunity to tell us what they think the barriers to being an effective supervisor are, and how the experiences of SLP for both supervisors and supervisees could be improved.

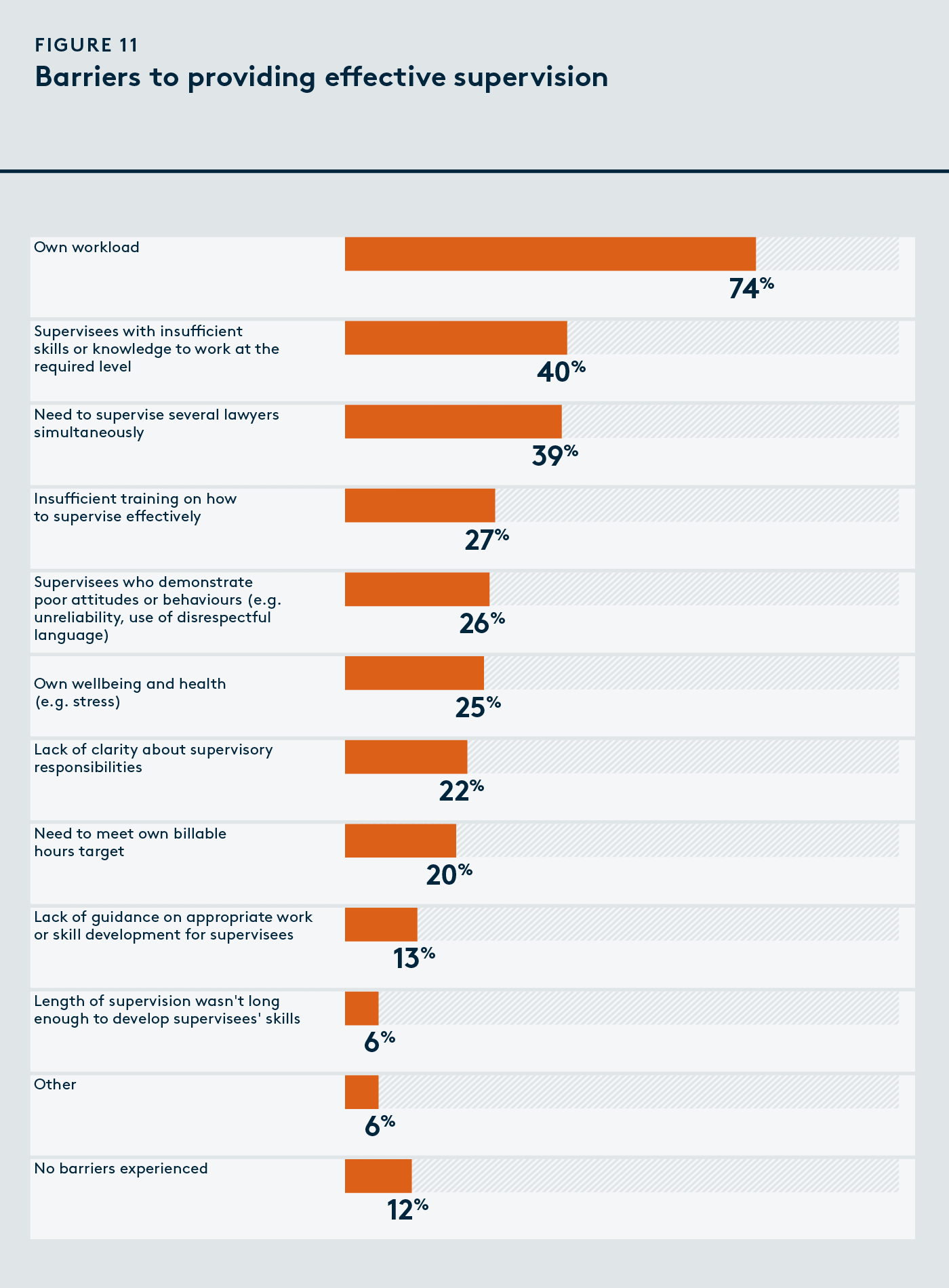

The majority of supervisors (88%) encountered a barrier to providing effective supervision at some point in their careers. The most common barrier was personal workload (74%), followed by:

- their supervisee’s lack of skill or knowledge (40%)

- having to supervise several lawyers at the same time (39%)

- the lack of effective training about how to supervise effectively (29%)

- poor supervisee attitudes or behaviour (26%)

- their own health and wellbeing (25%) (for more details, see Figure 11).

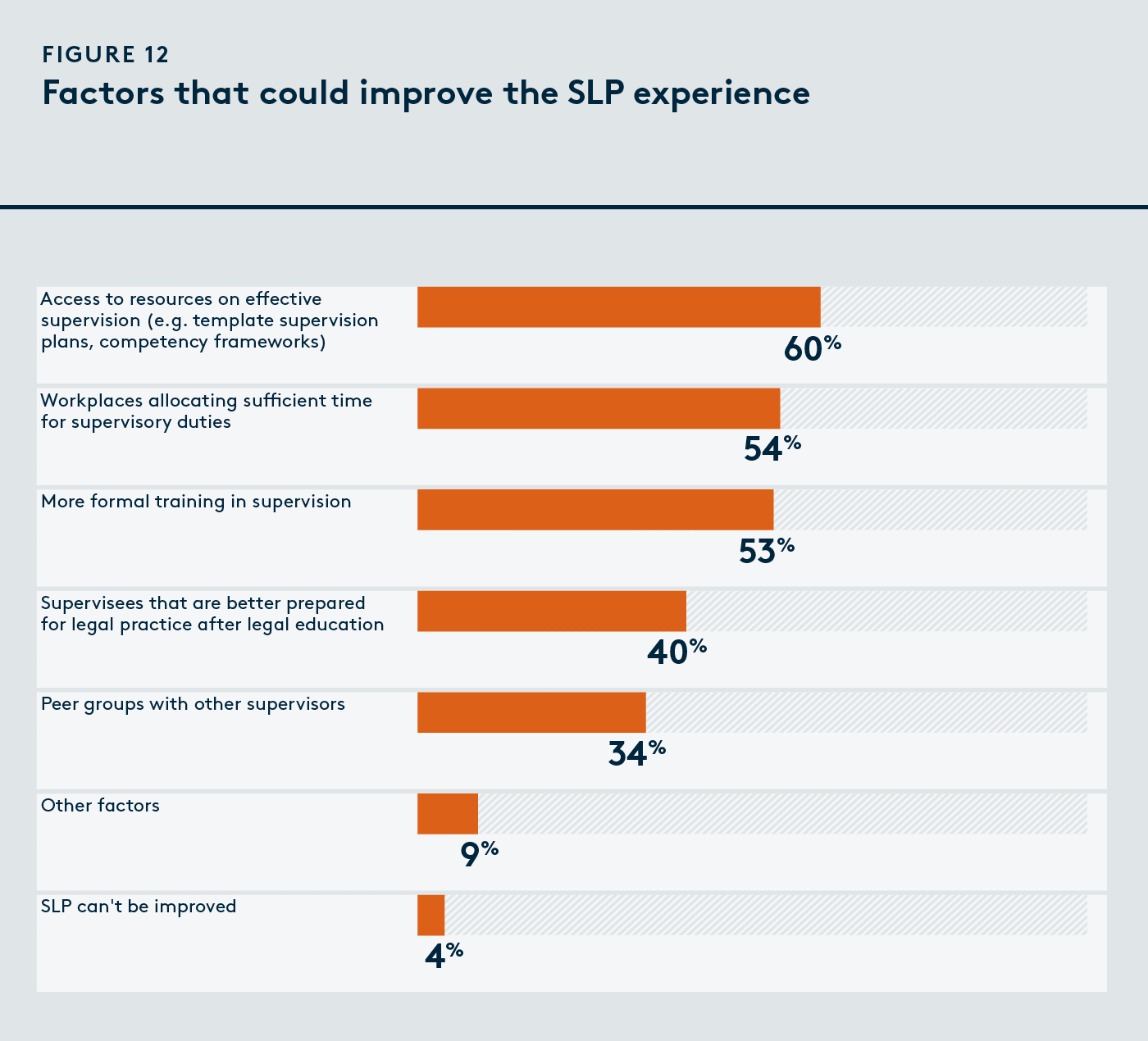

When asked which factors could improve the SLP experience for both supervisors and supervisees, 60% of supervisors identified access to resources on effective supervision (e.g. template supervision plans, competency frameworks) as a key opportunity. Over half (54%) said allocating enough time for supervision is an important factor, and 53% told us that more formal training in supervision would be helpful (for more details, see Figure 12).

Our next steps

This survey, and the survey we conducted in 2023, have given us invaluable insights into benefits and challenges of the SLP period, from the perspective of both supervisees and the more experienced lawyers who take on the responsibility of being a supervisor.

The findings from both surveys tell us that supervisees and their supervisors would benefit from more support to maximise what they can gain from SLP and reduce the challenges and barriers associated with supervision. In 2025 we will start developing tools and resources with the aim of helping the profession provide responsive and effective support to supervisors and their supervisees.

* Please note: the rounding of the data means that not all totals add up to 100%